Four decades have passed since reports of clergy sexual abuse first garnered widespread attention in the United States and abroad. In more recent years, the 2018 Pennsylvania grand jury report and 2019 Vatican summit have spurred initiatives to support new dialogue and research on religion and sex abuse. For example, Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., president of the University of Notre Dame, has committed up to $1 million to support new projects across campus. Among those research sites is the Cushwa Center, which has convened a group of American religious historians led by Kathleen Sprows Cummings, Robert Orsi, Peter Cajka, and Terence McKiernan.

Other Catholic institutions have also announced recent initiatives to kickstart the study of clergy sexual abuse, including the Catholic University of America, Fordham, Georgetown, Gonzaga, and Villanova. Similarly, in 2019, the Henry Luce Foundation funded a new project on “Religion and Sexual Abuse,” and the American Academy of Religion launched a seminar on “Contextualizing the Catholic Sexual Abuse Crisis,” which I have the honor to co-chair with Gonzaga theologian Megan McCabe.

I have been working with survivors since 2011, when I began my doctoral research on Linkup and SNAP, two advocacy organizations founded by American Catholic survivors in the late 1980s. My current book project, “Surviving Soul Murder,” builds on that history through interviews with survivors in California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania.

With an eye toward supporting these new initiatives and providing information to the many colleagues and Catholics who wish to learn more about the topic, I share this brief overview of the burgeoning interdisciplinary literature on clergy sexual abuse.

Before I begin, I want to acknowledge two of the choices that guide this overview. First, I focus here on authors who have completed extensive, book-length research on clergy sexual abuse. There are many more colleagues who have written shorter articles. To gather a sense of this broader literature, readers might seek out one of several extensive reading lists that are available online, such as Father Thomas Doyle’s bibliography on Catholic sexual abuse (170 pages as of its April 2020 edition).

Secondly, although most of these books are written by academic scholars, I begin by foregrounding some of the best work by survivors, journalists, and church whistleblowers. This is a deliberate choice to acknowledge the sacrifice that survivors have made. It is also historically grounded, because the activism of survivors and survivor-advocates has strongly influenced scholars’ subsequent interpretations of the Catholic scandal. Survivors had already generated a sustained, national public discourse on clergy sexual abuse by the early 1990s, ten years before Boston and more than a quarter century before the 2018 Pennsylvania grand jury report.

Survivors

Clergy sexual abuse is not a uniquely modern phenomenon. But it was widely ignored—along with broader experiences of sexual assault and incest—until the feminist movement of the 1970s spurred new social and legislative conversations. As American culture began to open up about the widespread prevalence of child sexual abuse, so too did Catholics who had been abused by priests and nuns.

During the 1980s, American Catholic survivors began to speak publicly. Allegations surfaced regionally, and it initially appeared that clergy abuse was isolated to a relatively small number of dioceses. By the 1990s, however, survivors and journalists spotted a broader trend, and they began to document the emerging scandal.

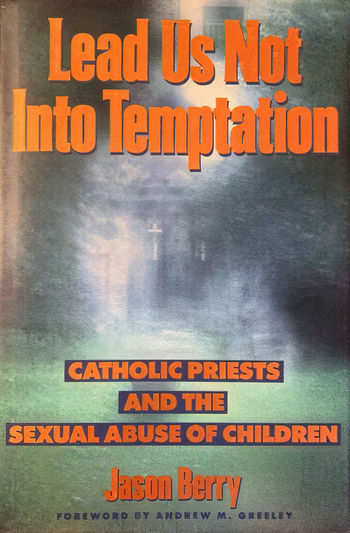

Many Americans first read about Catholic abuses through the reporting of Jason Berry, who covered the 1985 trial of Louisiana priest Gilbert Gauthe. Berry’s book Lead Us Not Into Temptation (Doubleday, 1992) built upon the Gauthe example and other cases to situate clergy abuse within broader debates over Catholic theology, clerical celibacy, and seminary formation. In doing so, Berry listened carefully to early survivors, including Jeanne Miller and Barbara Blaine.

After her son was abused in 1982, Miller reached out to the Archdiocese of Chicago for help. The chancery responded with a hush-money settlement, which left the Millers feeling broken and betrayed. After writing a thinly veiled memoir, Assault on Innocence (B&K, 1987), Miller appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show, Larry King Live, and other television talk shows. Survivors from across the country began reaching out to her for support. With the help of longtime friend Marilyn Steffel, who was the director of religious education at their suburban Chicago parish, Miller founded Linkup, one of the nation’s first Catholic survivor organizations.

Simultaneously, Catholic Worker Barbara Blaine began hosting self-help meetings for smaller groups of victims on Chicago’s South Side. Blaine’s group eventually became the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP). Spurred by Miller and Blaine’s leadership, other communities of survivors founded their own support organizations, including in Los Angeles, Cleveland, and greater Boston.

Frank Bruni and Elinor Burkett capture the energy of these early survivor organizations in their book A Gospel of Shame (Viking Penguin, 1993), which chronicles the advocacy of survivor leaders like Frank Fitzpatrick. In 1990, Fitzpatrick began taking out ads in regional newspapers throughout New England, asking “Do you remember Father Porter?” Over the following year, more than 90 of James Porter’s victims came forward. Fitzpatrick founded Survivor Connections, and in 1992 his story became the focus of a much-publicized episode of Primetime Live with Diane Sawyer.

In the fall of 1992, Linkup hosted a national gathering of nearly 500 survivors at a healing and advocacy conference called “Breaking the Silence.” And break it they did. Over the following decades, hundreds of Catholic survivors have come forward publicly to share their stories of intimate suffering and spiritual betrayal. Most of those stories are accessible through media coverage, unsealed documents from court cases, and, increasingly, through the public reports of grand jury investigations impaneled by state prosecutors. The website BishopAccountability.org has catalogued and indexed an astounding quantity of these reports, and it is an invaluable resource for both historians and laypersons who wish to begin work on the abuse scandal.

Readers who appreciate journalism’s strong, unencumbered style should, of course, also revisit the reporting of the Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” team, which has been distilled into their book Betrayal: The Crisis in the Catholic Church (Little, Brown and Co., 2002). Although much of the Globe’s original reporting can still be found online, Betrayal provides a gestalt that is more lucid and empathetic, especially in its renewed focus on victims’ families.

Although it is not always visible in news media coverage, many survivors are also acute analysts. I know from my ethnographic work just how robustly survivors contextualize their own abuse, and I often marvel at their critical awareness of the broader cultural dynamics at play in debates about the causes and meanings of clergy abuse.

One way to begin appreciating the depth of survivors’ knowledge is to read their own reflections, which are available both in single-author memoirs and in a growing number of edited volumes that compile reflections from multiple victims, such as J.M. Handlin’s Survivors of Predator Priests (Tapestry, 2005), Ruth Moore’s Survivors’ Lullaby (AuthorHouse, 2006), or Broken Trust (Crossroad, 2007) by Patrick Fleming, Sue Lauber-Fleming, and Mark T. Matousek. Handlin includes survivors who were abused in a wide range of Catholic contexts. Broken Trust is somewhat unique in its choice to foreground the reflections of abusive priests. Moore’s Survivors’ Lullaby focuses on Boston victims and stands out for its poignant insights into the tense, often painful relationship between survivors and lay reform movements like Voice of the Faithful.

Whistleblowers

There were also warning bells from within the Church, including the remarkable collaboration of Father Thomas Doyle, Roy Mouton, and Father Michael Peterson. These men met one another in 1984, through their mutual efforts to defend the Church during the Gauthe trial. Doyle was a Dominican priest and canon lawyer who kept the apostolic nuncio apprised of new developments in Gauthe’s case. Mouton was the lawyer hired by the Diocese of Lafayette to defend Gauthe. Peterson, the founder of the Saint Luke Institute, was consulted by the bishops on Gauthe’s psychological evaluation and treatment. Through their work together, these men learned that priestly pedophilia was a much more widespread problem, and they took it upon themselves to conduct more extensive research. They recorded their findings in a 92-page report titled “The Problem of Sexual Molestation by Roman Catholic Clergy: Meeting the Problem in a Comprehensive and Responsible Manner” (1985).

The Doyle-Mouton-Peterson report emphasized the enormous insurance, criminal, and financial liabilities that American dioceses might face over the subsequent decade. After unsuccessfully attempting to have the report included in the 1985 meeting of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, Doyle mailed photocopies to dioceses across the country. After his advocacy was met with silence and denial, Doyle transferred out of the apostolic delegation and became a Navy chaplain. During the past 30 years, he has been among the most outspoken and steadfast advocates of clergy sexual abuse victims. Among survivors, Doyle’s status as a whistleblower and living saint is rivaled only by that of A.W. Richard Sipe.

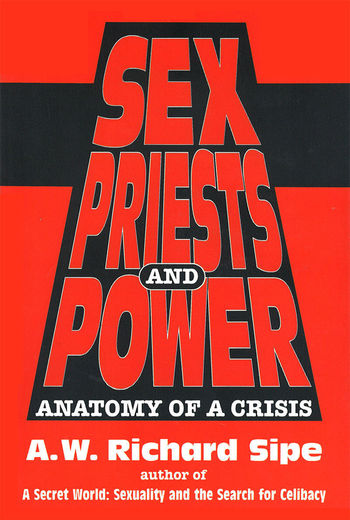

Sipe was a former Benedictine monk who became a psychotherapist for abusive priests. In the early 1980s, Sipe realized that only a fraction of his patients were able to maintain their vows of chastity, and he devoted the rest of his life to the study of celibacy and sexual abuse. Sipe approached these topics as qualitative questions. He published many articles and several books, including A Secret World (Brunner/Mazel, 1990) and Sex, Priests, and Power (Brunner/Mazel, 1995), which contend that the theology of celibacy fundamentally serves to mask the Church’s centralization of ecclesiastical authority. In his view, clergy abuse is only one of several symptoms that stem from the Church’s deeply gendered theologies of power and sexuality.

Through their advocacy work for survivors, Sipe and Doyle became close friends. They spoke together at survivor events throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, and eventually co-authored, with Patrick Wall, Sex, Priests, and Secret Codes (Volt, 2006), which analyzes the scandal through the disparate lenses of early Church writings, canon law, American civil law, and contemporary news reports. With astonishing clarity, this co-authored book lays bare the fact that Church leaders have, for centuries, been anxious about the prevalence of sexual relationships between priests and children. Of equal interest to Catholic historians, perhaps, Sex, Priests, and Secret Codes reprints the Doyle-Mouton-Peterson report in its entirety.

Theologians

The survivors and whistleblowers who came forward in the 1980s and 1990s were prophetic. They proclaimed painful truths, but most Catholics were unready or unwilling to hear them. There were a few Catholic academics, however, who listened attentively to survivors’ experiences of abuse and victimization.

Feminist theology and pastoral psychology were—as far as I can tell—the first fields to substantively attend to clergy abuse survivors. From 1976 to 2018, Marie Fortune authored or coauthored more than a dozen books on religion and sexual abuse. A theologian, ethicist, and minister, Fortune founded the interreligious FaithTrust Institute in 1977. I have found Fortune’s Is Nothing Sacred? (Harper, 1989) and Love Does No Harm (Continuum, 1995) particularly helpful for thinking through the ethical boundaries of pastoral care.

Fortune also edited the Journal of Religion & Abuse, which in 2003 published a special edition on “Sexual Abuse in the Catholic Church” (vol. 5, no. 3). The issue, which Fortune co-edited with W. Merle Longwood, showcased papers from a conference that they hosted at Siena College, including keynote addresses by Archbishop Harry J. Flynn and Bishop Howard Hubbard. This clerical core was augmented by remarks from survivors and critiques from theologians like Mary E. Hunt.

For readers who are interested in the ethics of pastoral boundaries, Fortune’s work pairs well with James Poling’s The Abuse of Power (Abingdon, 1991) and Carter Heyward’s When Boundaries Betray Us (Pilgrim, 1993).

I was first introduced to this constellation of ethicists by Cristina L. H. Traina. In her own book, Erotic Attunement (University of Chicago, 2011), Traina destabilizes some of the most hotly contested debates surrounding Catholic clergy sexual abuse by beginning, instead, with the inherently sensual and indisputably unequal relationship between a mother and her children. Sensual touch, Traina argues, can be essential for nurturing healthy relationships, and it is also central to healthy Catholic rituals and devotions.

Questions about the erotics of Catholic life also reverberate through the writings of Mark Jordan, whose recent books manage to provoke deep reflection on clerical abuse while rarely engaging explicitly with news accounts of the contemporary scandal. Jordan’s The Silence of Sodom (University of Chicago, 2000) and Telling Truths in Church (Beacon, 2003) excavate the foundational elisions of Catholic sexual ethics.

Pastoral and clinical psychology

While theologians have emphasized the ethical entanglements of clergy abuse, psychologists have focused on questions of providing treatment to abusive priests and their victims. Pastoral psychologists and clinical psychologists seem to diverge from one another, however, on the pivotal question of whether the Church has already instituted adequate reforms to protect future children.

Broadly speaking, pastoral psychologists have been concerned primarily with pragmatic reforms that could both protect future children and restore credibility to American bishops. Father Stephen Rossetti and Leslie Lothstein were among the early pioneers in this area. Rossetti’s edited volume Slayer of the Soul (Twenty-Third Publications, 1990) offers a limited but nevertheless striking glimpse of the collaborative exchanges that were still possible, 30 years ago, between abusers, survivors, bishops, and psychologists. In 1993, Father Rossetti served on the NCCB Ad Hoc Committee on Sexual Abuse; in 1994 he helped co-found the now-defunct Interfaith Sexual Trauma Institute at Saint John’s Abbey; and from 1996–2009, he was president of the Saint Luke Institute.

Thomas Plante has been one of the most prolific researchers in this area. In the late 1990s, Plante published several articles about clergy sexual abuse in the journal Pastoral Psychology and, over the following decade, he edited three books about clergy sexual abuse, each of which foregrounded issues of institutional reform and prevention: Bless Me Father for I have Sinned (Praeger, 1999), Sin Against the Innocents (Praeger, 2004), and Sexual Abuse in the Catholic Church (Praeger, 2011), which was co-edited with Kathleen McChesney, a former FBI agent whom the American bishops selected as the inaugural director of the USCCB’s Office of Child and Youth Protection. Sin Against the Innocents is my favorite of these edited volumes, because it ambitiously includes not only psychological perspectives but also essays by survivors, priests, nuns, journalists, whistleblowers, law enforcement agents, and theologians.

Whereas these pastoral psychologists have focused mostly on healing the Church, clinical psychologists have written more on the suffering and treatment of victims. Because of her compassionate theorization of survivorhood, Mary Gail Frawley-O’Dea’s Perversion of Power (Vanderbilt, 2007) is usually the first book that I recommend to colleagues who want to begin teaching about the clergy sexual abuse crisis.

In an accessible but critical tone, Frawley-O’Dea weaves together key insights from psychoanalysis, cultural anthropology, and Catholic history. Even as I disagree with some of the key arguments in Perversion of Power, I admire the way that Frawley-O’Dea foregrounds the perspectives of survivors, listens to whistleblowers like Sipe and Doyle, and echoes the advocacy of survivor-nonprofit leaders like Abuse Tracker’s Kathy Shaw, SNAP’s David Clohessy, and BishopAccountability.org co-founders Terence McKiernan and Anne Barrett Doyle. Frawley-O’Dea also co-edited, with Virginia Goldner, Predatory Priests, Silenced Victims (Routledge, 2007).

Whereas Frawley-O’Dea works from her clinical experience with victims, Irish psychotherapist Marie Keenan offers a rare glimpse into the challenges of providing care to abusive priests. In Child Sexual Abuse in the Catholic Church (Oxford, 2012), Keenan refuses to dichotomize victims and abusers, arguing instead that both parties need to be understood within the broader study of Catholic culture. Keenan’s book attempts an exhaustive analysis of many issues implicated in clergy abuse, including ecclesiology, clericalism, sexuality, and gender.

Sociology and cultural history

Sociologists have also produced ample literature on the Catholic scandal. In the 1990s, Anson Shupe was particularly prolific. A sociologist of religious criminality, Shupe spent much of his career focused on the transgressions of “bad pastors.” Shupe’s In the Name of All That’s Holy (Praeger, 1995) lays out several theories for why so many clergy seem to go astray. In his later books, such as Spoils of the Kingdom (Illinois, 2007), Shupe delves deeper into some of the particular challenges of Catholic clerical abuse, including his effort to apply social exchange theory in order to explain priestly patterns of secrecy and blackmail. I find his single-authored works less interesting than his edited volumes on clergy abuse, especially Wolves within the Fold (Rutgers, 1998).

Shupe identified “clergy deviance” in many religious traditions, but Catholicism was his most consistent focus, which mirrored the broader American cultural discourse on clergy sexual abuse during the 1990s and early 2000s. One of the few scholars who has directly examined that trend is the cultural historian Philip Jenkins. Six years before the Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” reporting, Jenkins’ Pedophiles and Priests (Oxford, 1996) argues that the media was skewed in its focus on Catholic abusers. Although he attempts to extend sympathy towards survivors, Jenkins ultimately blames journalists for “constructing the crisis,” and he faults news teams for relying on anti-Catholic tropes and regurgitating stereotypes of the pedophile priest.

Jenkins elaborates his theory of media bias in The New Anti-Catholicism (Oxford, 2003), which seeks to contextualize the clergy abuse scandal within broader public outcry against Catholicism’s deeply gendered sexual ethics. I am not persuaded by Jenkins’ portrayal of American society as inherently anti-Catholic, and perhaps that is in part due to our generational divide—I grew up in a nation where more than half of the Supreme Court is Catholic, where one-fifth of the citizens and even more of its elected members of Congress are Catholic, and where Catholic universities and their football teams are national treasures. But that is not to say that I find fault in Jenkins’ theoretical framework of moral panic; in fact, I am quite persuaded regarding the role of sexual abuse allegations in causing moral panics about religious groups that are actually marginalized in our society, a phenomenon explored in Megan Goodwin’s Abusing Religion (Rutgers, 2020).

Like Plante and, more recently Peter Steinfels, Jenkins’ view is that the American bishops have already solved the problem of clergy sexual abuse, and that—at least since the passage of the USCCB’s Dallas Charter in 2002—children in Catholic parishes and schools are actually better protected than their secular counterparts. One way to read Jenkins’ work is as a public intervention aimed at thwarting what he perceives to be a thinly cloaked coalition of Catholic liberals and liberal anti-Catholics who are collectively leveraging survivors’ suffering in order to advance their own progressive agendas.

This question of whether survivors have been co-opted undergirds several more recent sociological studies of Voice of the Faithful (VOTF). Founded in the wake of the Boston Globe’s 2002 “Spotlight” reports, VOTF is a broad coalition of non-abused laypersons seeking to support both survivors and priests. Building on his prior work on the post-Vatican II reform group Call To Action, Father Anthony Pogorelc co-authored, with Willian D’Antonio, Voices of the Faithful (Herder & Herder, 2007), which contextualizes VOTF as a new religious social movement.

The framework of social movement theory also guides Tricia C. Bruce’s excellent book Faithful Revolution (Oxford, 2011), which provides even more texture into the ethos of VOTF. Bruce studies VOTF less as a Boston group than as a national network of Vatican II Catholics whose reform agenda mostly predated the clergy abuse scandal. There is much to admire about Bruce’s study, including her careful documentation of the fact that VOTF is a movement within the Church, even as its broad membership and sweeping agenda have tested the boundaries of what we might call—if I may borrow the phrasing of sociologist Michelle Dillon—American Catholic identity.

Even more recently, sociologists Patricia Ewick and Marc Steinberg published Beyond Betrayal, which empathetically charts the concerns of a single VOTF chapter in order to offer a case study into the national movement. Their research is all the more valuable because, over the past ten years, many—perhaps most—local VOTF chapters across the country have disbanded or disintegrated, as their founding generation ages toward the final stage of life.

Legal studies

In echoes of the increasingly litigious nature of American society, scholars of criminology and law have also produced considerable research into the contemporary Catholic sexual abuse scandal. The lengthiest of these have been reports commissioned by the secular authorities, including the 13 American grand juries that have released reports since 2002 (there have been six reports in Pennsylvania alone), and the three primary reports commissioned by the USCCB, all led by John Jay criminologist Karen J. Terry: The Nature and Scope of the Problem (2004), Supplementary Data Analysis (2006), and The Causes and Contexts (2011). All of these reports are available to download on a single BishopAccountability.org page.

In the United States, most child sexual abuse cases fall under the civil and criminal statutes of limitations (SOLs) set individually by each state’s legislature. Prior to recent reforms, many states had statutes that required child victims to come forward within just a few years of reaching adulthood in order to seek justice in court. In the 1990s and 2000s, Catholic survivors inspired legislators accross the country to dramatically expand their SOLs for sexual assault. Survivors in SNAP and Linkup, who lobbied and testified year after year in state capitols, deserve much of the credit for those changes, along with secular child advocacy organizations. Although its summaries of SOL laws are now outdated (because SOL reforms continue to expand), Marci Hamilton’s Justice Denied (Cambridge, 2008) provides an incisive guide to the ways that SOL reform has both shaped and been reshaped by the advocacy of Catholic survivors.

Like Hamilton, law school professor Timothy Lytton has published widely—both in scholarly journals and news media—on the role of litigation in shaping the Catholic scandal. Lytton’s Holding Bishops Accountable (Harvard, 2008) examines the role of the courts in framing clergy sexual abuse and its cover-up as an institutional, rather than individual, sin. Lytton applies his expertise in civil suits to explore the promise and limits of the judicial system in repairing survivors’ lives. In addition to monographs by these legal historians, innumerable case articles have been published in law review journals, dating back as far as the origins of the Catholic survivor movement in the early 1980s.

Priests

We need many more books that analyze the role of the courts in attempting to repair survivors’ souls. And yet, at the same time, our public fascination with litigation and multimillion-dollar settlements has overshadowed alternative critiques of clergy abuse, particularly the powerful criticisms offered by some prominent priests.

Donald Cozzens, for example, has written eloquently about the anguish that many priests feel, including their anger at bishops who continue to cover up and deny the problems that enabled widespread clergy sexual abuse. In Sacred Silence (Liturgical Press, 2002), Cozzens faults the American bishops for fostering an inward-facing culture of extreme clericalism and secrecy. In his companion volume, A Faith that Dares to Speak (Liturgical Press, 2004), Cozzens calls upon the institutional Church to make space for female voices and to listen to lay reform groups like Voice of the Faithful. Like Pogorelc and Bruce, Cozzens interprets the lay uprisings after 2002 as the exhalations of a generation of Vatican II Catholics who have long yearned for more transparency and lay power within the American Church.

Cozzens’ books pair well with the Australian bishop Geoffrey Robinson’s Confronting Power and Sex in the Catholic Church (John Garratt Publishing, 2007), which argues that the Church’s best chances for solving the abuse scandal are hiding in plain sight. The Gospels, spiritual discernment, and a return to the less-gendered ethics of the early Church can, in Robinson’s opinion, replenish and sustain a more transparent and egalitarian Catholicism in the coming century.

Cozzens and Robinson agree that the abuse scandal requires a more pastoral response from Church leaders. That assessment is echoed, even more powerfully, by Joseph Chinnici, O.F.M., a Franciscan priest whose When Values Collide (Orbis, 2010) is among the most careful and compelling books that I’ve read about the American clergy abuse scandal.

Chinnici’s book is nearly equal parts personal memoir, local case study, moral theology, and American Catholic history. The book is grounded in Chinnici’s own experience of trying to respond to both employees and survivors within his flock. In the early 1990s, when Chinnici was serving as a provincial minister for the Franciscans, widespread allegations of child sexual abuse began to surface within his province of Saint Barbara, which spans the western United States.

With great sincerity, it seems to me, Chinnici recounts how he tried to minister to victims and their communities. He then uses his efforts and failings as a starting point for critiquing the lack of an adequately pastoral response by the Church. The bishops leading most American dioceses, Chinnici argues, lost public credibility because they rejected pastoral mediation in favor of denial and litigation. The final chapters of the book turn to theological questions, including whether the Church can reform itself in a way that revitalizes lay participation.

American Catholic history

In 2002, as the scope of the scandal in Boston reached its full force, Notre Dame’s historians of American Catholicism did not mince words: these revelations of clergy abuse would necessitate a deep rethinking of our entire field. In his book In Search of American Catholicism (Oxford, 2002), Jay Dolan wrote, “There has been nothing like this in the history of American Catholicism.” In Catholicism and American Freedom (Norton, 2003), John McGreevy stated that “the sexual abuse crisis is the most important event in American Catholicism since Vatican II, and the most devastating scandal in Catholic history.” And in his 2002 USCCB address, Cushwa Center Director Scott Appleby told the bishops that the crisis cannot be understood apart from the broader context of American Catholic history.

Over the decades and up to today, however—almost 20 years after Boston and nearly 40 years since American survivors began coming forward in great numbers—historians of American Catholicism have published relatively little research on clergy sexual abuse. With the exceptions of Jenkins and Father Chinnici, I cannot think of any Catholic historians who have completed a book-length study devoted entirely to the abuse crisis. Our disciplinary silence is deafening.

At the same time, there have been some attempts to incorporate the scandal into our broader understandings of U.S. Catholic history. The abuse scandal sets the stage, for example, for the final chapter of Boston historian James O’Toole’s The Faithful (Harvard, 2008). And the scandal’s aftermath is a persistent specter that haunts the Boston Catholics who are resisting the shuttering of their parishes in John Seitz’s No Closure (Harvard, 2011). These authors intentionally foreground the crisis, even as they wait—with the rest of us—for research that examines and contextualizes clergy sexual abuse more directly.

To date, the most extensive historical writing has been done by Robert Orsi. In his essay within the edited volume The Anthropology of Catholicism (University of California, 2017), “What is Catholic about the Clergy Sex Abuse Crisis?” Orsi argues that we cannot understand Catholic history without studying clergy sexual abuse. Even more provocatively, the chapter “Events of Abundant Evil” within Orsi’s History and Presence (Harvard, 2016) asserts that certain Catholic beliefs and rituals are—at least in part—intrinsically abusive. Catholicism, Orsi concludes, “created this crisis out of its own future and within the tradition itself—and then it compounded the horror by refusing to listen to or believe [victims], or to take steps to protect them and other children.”

Breaking our silence

Survivors, as I mentioned earlier, held a national conference in 1992 called “Breaking the Silence.” My dissertation, which is titled after that event, studied the history of the early survivor movement in Chicago, and I hope that my ongoing research will create space for more victims’ voices within the study of American Catholic history.

It is time to break our disciplinary silence about clergy sexual abuse. Foremost—as I argued in a recent issue of American Catholic Studies—we must be accountable to survivors, and we must bear witness to the Catholic experiences of abuse that they have suffered. Our continued silence would amount to concealment and complicity.

It is in this spirit of accountability, I believe, that Notre Dame and many other Catholic institutions have launched major campus initiatives to better understand clergy sexual abuse. I look forward to this groundswell of future studies, and I am grateful to the Cushwa Center for encouraging scholars to continue to engage the challenges of sexual abuse, not only through our historical research but also in our own parishes, families, schools, and spiritual lives.

Brian J. Clites is a faculty member in the Department of Religious Studies at Case Western Reserve University, where he also serves as associate director of the Baker-Nord Center for the Humanities.

This article appears in the fall 2020 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.

Originally published by at cushwa.nd.edu on November 16, 2020.